Kevin Strickland Comes Home After 43 Years Behind Bars for a Crime He Didn’t Commit

A new Missouri law empowers prosecutors to right wrongful convictions. But the state attorney general is intent on standing in the way.

Cynthia Douglas didn’t recognize the man holding the shotgun the night her boyfriend and best friend were murdered.

It was around 7:30 p.m. on a Tuesday evening when four men entered Larry Ingram’s bungalow in Kansas City, Missouri, where Douglas was hanging out with Ingram, her best friend Sherri Black, and her boyfriend, Jack Walker. Douglas was the only one to survive what would later be described as an execution-style attack. She told police she recognized two of the assailants right away — Vincent Bell and Kilm Adkins — but the other two were a mystery. One was wearing something like a sack over his head. The other, the man holding the shotgun, was short with some facial hair, Douglas said.

The next day, however, Douglas appeared to change her mind. She told the cops she thought the man with the shotgun might be 18-year-old Kevin Strickland, an acquaintance of hers. She’d figured it out after describing the unknown assailants to her sister’s boyfriend. You know, he told her, the short one sounded like it could be Strickland, who lived two houses down from Bell. At first, Douglas said no way; she didn’t know Strickland to have facial hair. But ultimately, she came around to the idea. In 1979, Douglas’s testimony would be key to sending Strickland to prison with a life sentence, even though no physical evidence tied him to the crime.

Douglas died in 2015. But during a three-day hearing in Kansas City this month, Douglas’s friends and family said that not long after Strickland was convicted, Douglas realized she was wrong. For years she tried to get people to listen without success. “Mother, I picked the wrong guy,” Senoria Douglas recalled her daughter telling her. “I picked the wrong guy!”Join Our NewsletterOriginal reporting. Fearless journalism. Delivered to you.I’m in

For 43 years, Strickland remained in prison and maintained his innocence. It was only after Douglas’s death that the Midwest Innocence Project began investigating the case, which also caught the attention of the prosecutor’s office in Kansas City. Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker became convinced of Strickland’s innocence, and her quest to overturn the conviction prompted this month’s court hearing.

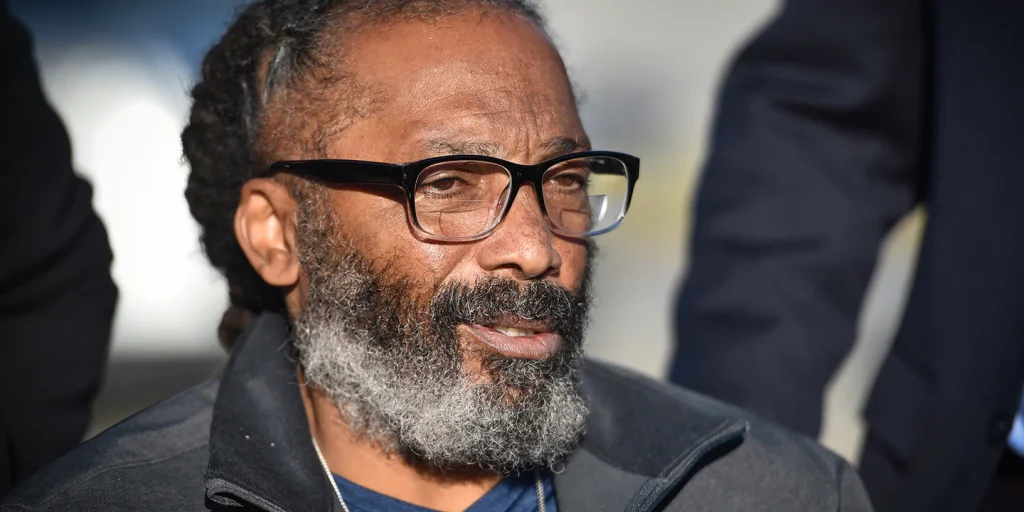

On November 23, presiding Judge James Welsh ruled that Douglas’s recantation was credible and the conviction could not stand. Just a few hours later, Strickland was released. “I didn’t think this day was going to come,” he said.

Until recently, this scenario would have been impossible, as Missouri prosecutors lacked a meaningful way to revisit a conviction they believe was wrongly obtained. But earlier this year, the state legislature passed a law intended to fix the problem. Strickland’s case was the law’s first test. “To say we’re extremely pleased and grateful is an understatement,” Baker said in a statement. “This brings justice — finally — to a man who has tragically suffered so, so greatly as a result of this wrongful conviction.”

The positive outcome came in spite of a powerful force intent on standing in the way: state Attorney General Eric Schmitt, whose office went to extreme lengths to keep Strickland locked up. In a court filing, Schmitt put his myopic view on full display, writing that Strickland was fairly tried and convicted. “For more than forty years,” he wrote, “Strickland has worked to evade responsibility for the murders.”

Schmitt has stubbornly defended a perversion of justice — and in doing so, has cast a shadow over the future of the state’s new law, designed to fix such miscarriages of justice. The pitched battle the attorney general’s office waged in Kansas City may have a “chilling effect” on prosecutors in smaller or more rural counties, said Sean O’Brien, a law professor at the University of Missouri, Kansas City. “And that may be the intent.”

Starting Off Wrong

On April 25, 1978, Douglas, Black, and Walker met up in the late afternoon and made their way to Ingram’s house. The friends, all in their early 20s, were smoking pot, drinking cognac, and watching TV when there was a knock on the front door. Two men, Adkins, 19, and Bell, 21, came into the house. Adkins grabbed a pistol that was on top of the TV and demanded money from Ingram. Ingram held craps games at the house, and days earlier, Adkins had lost money in a game he thought had been rigged with loaded dice.

Adkins ushered two others inside. One, the short guy, pointed a shotgun at Douglas and told her not to look at him. Douglas was ordered to tie up Walker, then Douglas and Black were tied together. The men continued arguing with Ingram, who was also bound, and eventually Adkins started firing, killing Ingram, Walker, and Black. The man with the shotgun fired as well; buckshot pellets tore through Black’s head and into Douglas’s knee. Douglas slumped over and played dead. The men rummaged around the house and left. Douglas wriggled herself free and went outside in search of help.

When police arrived on the scene, Douglas was sitting in a neighbor’s living room, hysterical and bleeding. She told them that Bell and Adkins were responsible, but she didn’t know who the other two perpetrators were. She repeated the information at the police station sometime after 3 a.m., when she gave her first formal interview.

The next day, however, Douglas called the cops to say Strickland had been the guy with the shotgun. She’d known Strickland casually for a couple of years, so when police asked her to view a lineup down at the station, she easily identified him.

Strickland was arrested and charged with murder. The state would seek the death penalty. Adkins and Bell, who fled to Wichita, Kansas, before being arrested, saw the news of Strickland’s arrest — and took it as a good sign. “That’s good,” Adkins told Bell. “’Cause they starting off wrong. They picking up the wrong man.”

Strickland was the first to stand trial. The state’s first attempt, in February 1979, ended in a mistrial after the lone Black juror refused to find him guilty. After the jury failed to convict, the prosecutor said he had been “careless,” according to a court filing, and wouldn’t again make the “mistake” of letting Black people onto the panel. A few months later, he was successful in seating an all-white jury, which found Strickland guilty after a three-day trial. He was sentenced to a “hard 50”: life without the possibility of parole for 50 years.

Win at All Costs

Seeing Strickland convicted of a crime they knew he didn’t commit apparently spooked Adkins and Bell, who pleaded guilty in exchange for 20-year prison sentences. During his allocution, Bell gave a lengthy account of the crime, in which he named his three accomplices. Strickland was not one of them. “Kevin Strickland wasn’t at that house,” he said. “I’m telling the state and society out there right now Kevin Strickland wasn’t there at that house.”“I’m telling the state and society out there right now Kevin Strickland wasn’t there at that house.”

Instead, Bell said that he committed the crime along with Adkins, a 21-year-old named Terry Abbott, and 16-year-old Paul Holiway. Adkins later confirmed Bell’s account in two separate affidavits. Abbott was never charged for the crime but is serving a life sentence in Colorado for an unrelated armed robbery. In 2019, Abbott told an investigator for the Midwest Innocence Project, “There couldn’t be a more innocent person than Strickland.”

Holiway was never charged, nor was his possible role in the crime ever investigated. Holiway did not respond to an email from The Intercept.

As the years went on, Douglas’s role in sending Strickland to prison weighed heavily on her, friends and family say. Finally, in 2009, Douglas emailed the Midwest Innocence Project with the subject line “Wrongfully charged.”

Roughly a decade later, after the organization asked the Jackson County Prosecutor’s Office to agree to fingerprint testing on the shotgun, the office’s Conviction Integrity Unit started its own review of the case. This past June, Baker, the prosecutor, said her office had determined that Strickland was innocent. “My job is to protect the innocent. And often, prosecutors show hubris, right? You’ve probably seen me show some of that from time to time,” she said during a press conference. “And today, my job is to apologize. It is important to recognize when the system has made wrongs. And what we did in this case was wrong.”

The way Baker saw it, it was also her duty to see that the wrong was righted. In Missouri, that’s easier said than done. State law had long precluded local prosecutors from taking action to overturn wrongful convictions, and the attorney general’s office fought hard to keep it that way.

That’s true in the case of Lamar Johnson, who has been in prison since 1994 for a murder in St. Louis that no one believes he committed, including elected Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner. Still, Schmitt’s office insisted that Gardner lacked any power to help Johnson. When the case wound up at the Missouri Supreme Court in 2020, the attorney general’s office argued that giving a local prosecutor the power to right a wrongful conviction had “the potential to undermine public confidence” in the criminal legal system.

None of this surprised O’Brien, the law professor, who has worked on numerous exonerations over the last three decades. The attorney general’s office has reflexively opposed innocence claims “forever, for as long as I’ve been a lawyer,” he said. “I have never seen this office admit that a mistake was made.”

At times, this win-at-all-costs culture has manifested in obscene and absurd ways. In 2003, the Missouri Supreme Court considered the case of Joseph Amrine, who was on death row for a murder he didn’t commit. The attorney general’s office argued that Amrine, who had exhausted his appeals, should be barred from having his innocence claim considered by the court. Are you suggesting that “if we find that Mr. Amrine is actually innocent, he should be executed?” one of the judges asked. “That’s correct, your honor,” an assistant attorney general replied.

In Johnson’s case, the state’s high court ultimately ruled that there wasn’t a mechanism within Missouri law that allowed prosecutors to take legal action in local courts to undo an injustice that their offices were responsible for. The chief justice called on the state legislature to take charge.

Under Missouri’s new law, local prosecutors can file a motion to vacate a wrongful conviction in the court where a person was originally tried. The reviewing judge is required to hold a hearing and decide whether there is “clear and convincing evidence of actual innocence” or a constitutional violation that would undermine the conviction.

But there’s a catch: The law also requires that the attorney general’s office be given the opportunity to take part in the hearing, by questioning witnesses and arguing its position.

Baker was ready to file for a hearing in Strickland’s case the day the new law took effect. Predictably, Schmitt’s office was also ready with a challenge, which included an argument that the entire Jackson County bench should be disqualified because the presiding judge had told Baker’s office that he agreed Strickland was innocent. In order to avoid “even the appearance of partiality or impropriety,” the Missouri Supreme Court blocked the local judges from hearing the case and instead appointed a retired appeals court judge, Welsh, to preside over the hearing.

Trauma and Memory

On the morning of November 8, reporters waited for 62-year-old Strickland to arrive at the Jackson County courthouse. He’s a slight man, just 5-foot-3, and now relegated to a wheelchair because of spinal stenosis. Because of his condition, Strickland can only stand for minutes at a time, his lawyers said.

Over the next two days, Baker and lawyers for Strickland called a series of witnesses who took aim at the heart of the case: the alleged eyewitness identification by Cynthia Douglas back in 1978. They included a group of friends and family who were unequivocal in saying that Douglas knew she’d identified the wrong guy. The weight of the struggle, combined with ongoing grief over losing her best friend to murder, the witnesses said, had hastened Douglas’s untimely death at age 57.

Douglas’s older sister, Cecile Simmons, testified that Douglas reached out to numerous officials about her mistake, including now-deceased former Gov. Mel Carnahan and former Jackson County prosecutor-turned-U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill. But no one listened. Douglas told Simmons about how the police had pressured her to identify Strickland — and said that if she didn’t cooperate, all the perpetrators might go unpunished. At one point, Simmons said, Douglas tried to recant to the prosecutor’s office but was met with threats of arrest and perjury charges. “It’s hard to comfort someone when they’re not at peace,” Simmons testified. “This just haunted her.”

Eric Wesson, a childhood friend of Douglas’s and publisher of the city’s legendary 102-year-old Black newspaper The Call, said Douglas had come to him multiple times during the 2000s fretting over what to do. He helped her outline what she should write in an email to officials. She’d tried contacting people from her personal email address, he said, but decided maybe she should try her work address instead. She thought the imprimatur of the Jackson County Family Court system, her employer, might get someone’s attention, even though she joked that it could also get her fired for its improper use. She ultimately used her work address to write to the Midwest Innocence Project.

The evidence of Strickland’s innocence went beyond the witness testimony of people Douglas had confided in over the years. Douglas told the cops that the guy with the shotgun had hair that was “natural,” but when they picked up Strickland the next morning, his hair was done in signature braids. And then there was the shotgun, recovered later in a ravine near a Pepsi plant. It had fingerprints on it, but they did not match Strickland. A fingerprint expert testified that, at the attorney general’s request, she also reviewed 60 latent prints recovered from the crime scene, and none of them belonged to Strickland.

In all, the lawyers advocating for Strickland’s release presented a cohesive narrative of how things went sideways in the case, ending in a wrongful conviction. The attorney general’s case, meanwhile, was a contradictory mess — like a chaotic tie-dye of Jell-O tossed against a wall; none of it seemed to stick.

The three assistant attorneys general on the case repeatedly suggested that the email Douglas sent to the Midwest Innocence Project was a fake. How her work email would’ve been spoofed and by whom wasn’t clear, though the implication seemed to be that Strickland was behind this — even though he was in prison and without access to a computer.

One of the attorneys, Christine Krug, tried to damage Wesson’s credibility by harping on the fact that he’d done time in prison decades ago. Another, Greg Goodwin, implied that Simmons was motivated to lie and say her sister had recanted because Simmons had lost friends over Douglas’s role as a witness for the prosecution. And he insinuated that Simmons was inclined to help Baker because she was somehow dazzled by meeting an elected official. Simmons shot him down. When Baker showed up at her house unannounced, “I didn’t answer the door,” Simmons said. “I called my husband and said, ‘There’s a white lady at the door. I don’t know who it is, but it’s probably not good.’”

Krug also attempted to undermine Dr. Nancy Franklin, a retired psychology professor specializing in memory and eyewitness identification. Franklin had reviewed the case at the request of the Midwest Innocence Project and concluded that Douglas’s identification of Strickland was “extremely unreliable.” While Franklin made clear in her testimony that she had taken Strickland’s case pro bono, Krug went on about how much money Franklin usually gets paid for expert consultation. It was the kind of witness badgering, full of manufactured outrage, that prosecutors often deploy in front of a lay jury. But this hearing was before a judge, and it seemed to fall flat with Welsh.

Vindication and Disbelief

Tricia Rojo Bushnell, the executive director of the Midwest Innocence Project, helped Strickland out of his wheelchair so he could take the stand at the hearing. His hair is thinning now but still pulled back into braids. He wore a red T-shirt under orange prison scrubs. One of his hands was attached to a chain around his waist.

“I had absolutely nothing to do with these murders,” he said. “By no means was I anywhere close to that crime scene.”

After he was charged, Strickland was offered a plea bargain, he said, but he didn’t take it — even though he was facing the death penalty. He just couldn’t take responsibility for a crime he didn’t commit. He said he knew the system worked. He believed he would be “vindicated,” he said. “That I wouldn’t be convicted of something I didn’t do.”

More than four decades later, and despite the efforts of the attorney general’s office, Strickland has finally found that vindication. In his ruling, Welsh rejected the attorney general’s argument that Douglas’s recantations were nothing more than hearsay peddled by untrustworthy friends and family. “The recantations Douglas made to her family and friends are reliable,” he wrote. “They were numerous and consistent.”

He also found credible the statements by Bell and Adkins averring that Strickland played no part in the triple murder and concluded that Strickland’s conviction rested solely on Douglas’s faulty identification. “Under these unique circumstances,” he wrote, “the court’s confidence in Strickland’s conviction is so undermined that it cannot stand.”

The attorney general’s response to Welsh’s ruling was clipped: “In this case, we defended the rule of law and the decision that a jury of Mr. Strickland’s peers made after hearing all of the facts in the case,” spokesperson Chris Nuelle said. “The court has spoken; no further action will be taken in this matter.”

Whether the outcome in Strickland’s case means the law that led to it will continue to work as intended remains to be seen. Some prominent attorneys in Missouri have already expressed skepticism, saying that the attorney general has been given too much power to stymie the process.

According to O’Brien, prosecutors across the state have paid attention to the story unfolding in Kansas City, including Gardner, the city of St. Louis circuit attorney. A spokesperson for Gardner did not respond to a question about whether she plans to use the law to exonerate Lamar Johnson, though it seems reasonable that she will. In a statement, Gardner said that her office “continues to move forward with diligence in its effort to ensure that Mr. Lamar Johnson receives the justice he deserves.”

Johnson’s case was marred by police and prosecutor misconduct. And, as in Strickland’s case, the two men responsible for the murder Johnson is in prison for have admitted their guilt, saying Johnson played no role. One of the men has never been charged in connection with the case; by standing up for Johnson, he put himself on the hook for a murder conviction.

But while prosecutors like Baker, Gardner, and St. Louis County’s Wesley Bell have the personnel and budgets to wage a battle they know the attorney general will fight, Missouri’s smaller jurisdictions simply don’t have those resources, O’Brien said. And Schmitt’s aggressive stance, which Baker called “prosecutorial malpractice,” may discourage others from even trying to rectify injustices in their jurisdictions. “It’s kind of rare, but we do see exonerations from rural counties,” O’Brien said. “And if I’m a prosecutor in a one-horse county, am I going to invite this fight?”

Strickland was watching TV on Tuesday morning when a news alert flashed with word of Welsh’s ruling; his fellow prisoners started cheering. Outside the prison, he told reporters he was in “disbelief” about finally being freed.

Strickland’s brother told the Kansas City Star that he was “just galactically overwhelmed” to learn that Strickland would finally be coming home. It will be the first time he has been home for Thanksgiving in more than four decades.

But Strickland’s battle is far from over. Missouri law only allows the state to compensate people exonerated by DNA, who account for roughly 19 percent of the nearly 2,900 exonerations nationwide since 1989. So there is no immediate way for the state to begin to repair the damage it has done. (And even when a person does qualify, the compensation is paltry: $50 per day of incarceration, capped at $36,000.)

O’Brien said that the only thing the attorney general accomplished by fighting Strickland’s release was to increase the toll of his wrongful conviction: The office’s efforts to stall the case and then block the local judges from considering it meant that Strickland was unable to see his mother before she died and wasn’t allowed to attend her funeral. “With all his sound and fury,” O’Brien wrote in an email to The Intercept, all “Schmitt did was delay Kevin’s release until his mother was no longer alive to see it.”

Strickland will be staying with his brother for a while, and the Midwest Innocence Project has set up a GoFundMe campaign to help pay for basic needs as he adjusts to life outside prison. As O’Brien wrote, “This joyful day is dimmed by the realization that he exits prison … with nothing.”